In the early part of 1999 a rather special lot came up at an auction in Sussex.

I was summoned late at night to be there by 10.30 next morning because, in

the words of the local Vintage Group member who alerted me to it, it was 'very

exciting'. He was right. When I got to see it, stuffed away in a general auction

of not very distinguished furniture and fittings that looked as though they

had come from a series of house clearances, I began to shake. Not only were

there 16 model yacht hulls of various types from large plank on frame models,

to a range of toy boat hulls of several types and sizes, there were also several

cabinets and a number of trays, like printers formes, stuffed with fittings

of every possible description. Some of these were for model yachts, including

nickel plated mast tubes and bowsprit fittings and a range of weighted rudders

of different sizes and types, together with lots of hooks and bowsies. The

great bulk of the stock, however, was for scale models of merchant vessels

both sail and steam. There were boxes and boxes of blocks and a whole range

of porthole glasses and rigols in different sizes, sufficient to equip many,

many models.

Clearly this was the remnant of the workshop of a very serious modeller, probably

a professional. As I was examining the range of fittings, I discovered that

some of the cardboard boxes had trade cards attached to them that showed that

all this had come from the workshop of William Paxton in Aldersgate Avenue

in the City. I already knew quite a bit about Paxton, who had traded as a

professional model maker from various addresses in the East End of London

from the 1880s onwards, ending up in Aldersgate Avenue, presumably to be closer

to his major customers.

His main line of business was large and elaborate display models of the sort

that used to be found in the windows of shipping companies, which were alleged

to cost up to £500 a piece at the end of the 19th century. He was also

a designer and builder of very serious model yachts to the Rating Rules of

the day, which he sailed as a member of MYSA on the Round Pond. A few of his

designs were published in around the turn of the century, but no identifiable

boats from his hand had come to light.

A third string to his bow was the manufacture of toy sailing boats and most

of the hulls in the auction were from this side of his work. An interview

with him in The Yachtsman towards the end of his career suggested that he

made 300 dozen small sailing boats over the winter for sale through toy shops

in the summer. This sounds an enormous number for a one man outfit, who had

other, and presumably more profitable, work to do, but it ties in well with

the claimed output of another London professional builder, George Sanderson.

In 1877 Sanderson employed at least 15 people in his workshops in Berwick

Street and turned out a claimed 10,000 models a year, using five hundred 12

foot lengths of 3 inch deal and eight tons of lead in the process.

What was sold at the auction was said to have come from a recent house clearance

in East London and was clearly the remnants of Paxton's workshop. Presumably

it was abandoned when he went out of business, probably in the very early

years of the 20th century, and had lain in the home of some descendant for

close on a century. It seems likely that he ceased to trade in the very early

years of the 20th century, since the comprehensive selection of yacht fittings

had several sorts of weighted rudder, but nothing that looked like a Braine

gear, introduced in 1904. A modeller as serious as Paxton would not have ignored

this technical advance.

All the hulls were unfinished and, with one exception, very obviously damaged.

They would have been unsaleable, even in a clearance situation, as would have

been the vast collection of miscellaneous bits and pieces. Most of the hulls

were clearly for toy boats and with each of these something had visibly gone

wrong while they were being built and the hull had been laid aside because

it was quicker to make another one than to try to rectify the error. Some

had warped, some had been damaged in the carving of the hull. One had a huge

knot in the quarters, which was on the point of falling out when I got to

it. The hulls had probably survived exactly because they were unsaleable.

The lot was bought by Joshua Ritchie, a member of the Vintage Model Yacht

Group who also deals in old boats and boat bits and pieces. I dropped out

of the bidding some way below the eventual hammer price, but as a result of

some negotiation with Joshua and the trading of other boats from my own collection,

I was able to lay hands on three of the hulls.

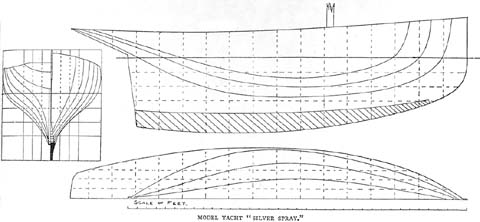

The boats I secured were two versions of a straight stemmed cutter, one very

small, about 12 inches overall, the other 22 inches, and a 20 inch schooner

hull of great elegance. The cutters were identical in form and very similar

to one of Paxton's larger racing yachts, Silver Spray from the 1880s, published

in The Yachtsman in 1893 and again in 1908. Silver Spray was a 36 inch waterline

boat to the MYSA Rule.

All the toy boats that I acquired shared the same general approach and had

a number of common fittings. The bowsprit bitts, for instance, were in each

case cut from hardwood and fitted through a slot in the deck. As I was able

to get at the underside of the deck on the small cutter I was able to see

that this fitting was retained by a small length of wire and a large gob of

animal glue. Similarly the sheet horses, in thin iron wire, had been fitted

through the deck and secured by bending the ends over before the deck went

on. Apart from these, there were no fittings other than plain pieces of dark

hardwood, probably mahogany, to represent hatches.

I decided to restore the smallest one first, with a view to getting the rig

right on the small version before I had a go at the larger cutter hull. I

also wanted to show her off at the Clapham meeting in September, and here

was the beginning of a disaster.

Alone of the three hulls, this one was carved from a single piece of deal

It also came with its deck separate from the hull. ]The others had been nailed

down with iron nails over a hundred years ago and were quite immovable. The

hulls were all well finished outside, but the small one showed fairly crude

work inside, and a very heavy build, with hull walls at least ¼ inch

thick. This is very heavy for so small a boat, but leaves plenty of room for

the odd error in carving and is amply strong enough for a child to play with.

The total weight of this small hull was about two pounds, which is a lot for

so small a boat, but there was a substantial lump of lead on the keel, possibly

as much as a pound, so she had a respectable ballast ratio of about 50%.

The hull was finished inside and out with a dark grey, undercoat and needed

a fair amount of filling and sanding before it was good enough by my standards.

She undoubtedly had far more TLC lavished on her than she would ever have

had from Paxton himself, but he was in business and would have been hard put

to charge more than a shilling for a boat of this type. The hull was eventually

finished in black and indian red, with a touch of blue on the inside of the

low bulwarks.

The deck was originally white and under the accumulated

filth of ages simply lined in pencil. As the white turned out to be of whitewash

or distemper, it all came off when I attempted to clean it up with a damp

rag. Clearly, Paxton had intended a coat of varnish before she went on sale.

So it was repainted in a pale cream and relined.

There was no mast step, so I had to make a simple wooden fitting to take the

foot of the mast. Getting it in the right place was a bit of a struggle, and

in the end it was done by fitting the deck temporarily and jury rigging the

mast. This enabled me to check that it was vertical in the thwartship direction

and at the appropriate rake, before the glue under the step went off.

The deck wasn't a very good fit on the hull as it had split,

shrunk and warped over the years. I backed the split with some heavy aircraft

tissue. Because of the warp in the deck, it would have needed a lot of filler

and a lot of work to make a good bedding fit for it. So I didn't bother, and

reasoned that though some water would get in, all would be well if I poured

it out regularly through the bung I had fitted in the deck. I was in a hurry

to finish in time for Clapham.

The rig was put together more or less by eye, with sails made from cotton

and bound with sticky back terylene. Anything to avoid the need to use a sewing

machine. It turned out to be about right, though I didn't get round to trying

the topsail that I had made for her. The sheet horses, gunwhale eyes and the

bowsprit gammon iron were bent up from brass wire and superglued into holes

drilled to give a driving fit. All the eyes needed for the rigging were made

the same way because even the smallest available screw eyes looked a bit heavy

on so small a boat.

The boat had clearly been intended to have a weighted rudder, so I put a pair

of pintles into the stern post and made a suitable rudder. The approved way

of doing this, when weighted rudders were the thing to use, was to put a few

small screws into the rear of the wooden part and then to cast the lead directly

onto these. Though it all went together quite easily, the rudder turned out

to be too heavy for the job and had the boat survived the lead portion would

have been cut down, or a new one made.

Here is a sequence of photos showing how the

casting was done. Note the use of the spirit level to see that the base board

is true. The sealant round the strip of ply that is forming the mould for

the lead is ordinary putty; plasticene is equally effective. You will see

that the photos show the use of protective gloves and all that, which you

should always use when working with molten lead, even in small quantities.

The other precaution that you must take is to ensure that the mould that you

are pouring into is perfectly dry. If you get this right, you won't need protection,

but it's not a risk worth taking, because the very smallest amount of damp

will turn into large quantities of steam capable of throwing molten lead over

large distances.

The day came and she sailed very effectively,

if slowly, across the pond, taking in quite a bit of water. No problem, I

just poured it out again. Then towards the end of the day, I put her in again

to take some photos. The wind had swung a bit and instead of going across

the pond, she set of on a slow and stately traverse of the length. She was

on the water a good deal longer than in crossing the width, the popple kept

coming over the side and she filled up and sailed under, just about in the

middle of the pond. Attempts at recovery proved unsuccessful, though they

did crown the day for my granddaughter, then two and a half. Not only did

she get to sail her own boat for the first time, she had the enormous pleasure

of seeing grandpa get a wet bum. Let this be a lesson to us all.

Russell Potts

|